History of Prince Edward Island

| Part of a series on the |

| History of Canada |

|---|

|

The history of Prince Edward Island covers several historical periods, from the pre-Columbian era to the present day. Prior to the arrival of Europeans, the island formed a part of Mi'kma'ki, the lands of the Mi'kmaq people. The island was first explored by Europeans in the 16th century. The French later laid claim over the entire Maritimes region, including Prince Edward Island in 1604. However, the French did not attempt to settle the island until 1720, with the establishment of the colony of Île Saint-Jean. After peninsular Acadia (present-day Nova Scotia) was captured by the British in 1710, an influx of Acadian migrants moved to areas still under French control, including Île Saint-Jean.

In 1758, the British gained control of the island as a result of the Ile Saint-Jean Campaign during the Seven Years' War. Shortly thereafter, British forces began to deport a number of Acadians from the island. The island was formally established as the British colony of St. John Island in 1769, later renamed to Prince Edward Island in 1798. Although the colony's capital hosted one of the conferences that led to Canadian Confederation in 1867, the colony itself did not enter Canadian Confederation until 1873.

Early history

[edit]Prince Edward Island was first inhabited by the Mi'kmaq people, who have lived in the region for millennia.[1] They named the island Epekwitk (the pronunciation of which was changed to Abegweit by the Europeans), meaning "cradle on the waves."[2] The Mi'kmaq mythology is that the island was formed by a great spirit placing some dark red clay which was shaped as a crescent on the pink waters. There are two Mi'kmaq First Nation reserves on Prince Edward Island today.

French colony

[edit]

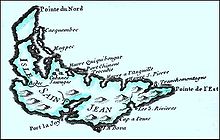

In 1604, France claimed the lands of the Maritimes and established the colony of Acadia. After the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713, the island was called Île Saint-Jean.[3] The first French settlers arrived in 1719 on a ship wrecked at Naufrage. The settlers lived primarily at Port-LaJoye and Havre Saint-Pierre (St. Peter's Harbour).[4] At Port-LaJoye there was an administrative unit and a garrison, detached from Louisbourg, where sat the government for both Ile Royale and Île Saint-Jean. While new settlements were established along the Rivier-du-Nord-Est and at but Havre Saint-Pierre remained the largest population throughout the French occupation of the Island.[5]

King George's War

[edit]After the Siege of Louisbourg (1745) during King George's War, the New Englanders also captured Île Saint-Jean (Prince Edward Island). An English detachment landed at Port-la-Joye. Under the command of Joseph de Pont Duvivier, the French had a garrison of 20 French troops at Port-la-Joye.[6] The troops fled and New Englanders burned the capital to the ground. Duvivier and the twenty men retreated up the Northeast River (Hillsborough River), pursued by the New Englanders until the French troops received reinforcements from the Acadian militia and the Mi'kmaq.[7] The French troops and their allies were able to drive the New Englanders to their boats, nine New Englanders killed, wounded, or made prisoner. The New Englanders took six Acadian hostages, who would be executed if the Acadians or Mi'kmaq rebelled against New England control.[7] The New England troops left for Louisbourg. Duvivier and his 20 troops left for Quebec. After the fall of Louisbourg, the resident French population of Ile Royal were deported to France. The Acadians of Ile Saint-Jean lived under the threat of deportation for the remainder of the war.[8]

Battle at Port-la-Joye

[edit]The New Englanders had a force of two war ships and 200 soldiers stationed at Port-LaJoye. To regain Acadia, Ramezay was sent from Quebec to the region. Upon arriving at Chignecto, he sent Boishebert to Ile Saint-Jean on a reconnaissance to assess the size of the New England force.[9] After Boishebert returned, Ramezay sent Joseph-Michel Legardeur de Croisille et de Montesson along with over 500 men, 200 of whom were Mi'kmaq, to Port-LaJoye.[10] In July 1746, the battle happened near York River.[11] Montesson and his troops killed forty New Englanders and captured the rest. Montesson was commended for having distinguished himself in his first independent command.[12]

Acadians

[edit]

During Father Le Loutre's War, at the beginning of the Acadian Exodus from mainland Nova Scotia, many Acadians migrated to the Island. The population increased dramatically from 735 to approximately three thousand. New settlements began at Pointe-Prime (Eldon), Bedec, and other places.[5]

The British captured Port Royal, the capital of Acadia in 1710, and established Nova Scotia in the peninsular part of Acadia. Over the next forty-five years, the Acadians refused to sign an unconditional oath of allegiance to Britain. During this time period, Acadians and Mi'kmaq participated in various militia operations against the British and maintained vital supply lines to the French Fortress of Louisbourg and Fort Beausejour.[13] During the French and Indian War (the North American theatre of the Seven Years' War), the British sought both to neutralize any military threat Acadians posed, and to interrupt the vital supply lines Acadians provided to Louisbourg, by deporting Acadians from the region.[14]

Once the first wave of the Expulsion of the Acadians began in mainland Nova Scotia, Acadians arrived on the Island as refugees. After the Siege of Louisbourg (1758), the second wave of the expulsion began. On the eve of 1758, the population had grown to almost 5000.[15] Commander Rollo accomplished the Ile Saint-Jean Campaign. One of the most dramatic removals was of Noel Doiron and his family from Eldon.

British colony

[edit]The British claimed dominion over all of the Maritimes in 1763. A separate colony on Prince Edward, named "St. John's Island" was established on June 28, 1769, after determined lobbying by the island's settlers.

American Revolutionary War

[edit]

During the American Revolutionary War, Charlottetown was raided in 1775 by a pair of US-employed privateers.[16] Two armed pirate schooners, Franklin and Hancock, from Beverly, Massachusetts, made prisoner of the acting Governor Phillips Callbeck, and Justice of the Peace, and Surveyor-General Thomas Wright, at Charlottetown, on advice given them by some Pictou residents after they had taken eight fishing vessels in the Gut of Canso.[17]

During and after the war, the colony's efforts to attract exiled Loyalist refugees from the United States met with some success. Walter Patterson's brother, John Patterson, one of the original grantees of land on the island, was a temporarily exiled Loyalist and led efforts to persuade others to come. The new British colony of "St. John's Island", also known as the "Island of St. John", was settled by "adventurous Georgian families looking for elegance on the sea. Prince Edward Island became a fashionable retreat in the 18th century for British nobility".[18]

New names

[edit]In 1798, Great Britain changed the colony's name from St. John's Island to Prince Edward Island to distinguish it from similar names in the Atlantic, such as the cities of Saint John and St. John's. The colony's new name honoured the fourth son of King George III, Prince Edward Augustus, the Duke of Kent (1767–1820), who was then commanding British troops in Halifax. (Prince Edward later became the father of the future Queen Victoria.) The majority of the colony was owned by absentee British landlords such as the shipping magnate Samuel Cunard. Protracted disputes, which lasted until Confederation, arose between the colonial office, tenants and the absentee landlords who owned most of it.[19]

Towards Confederation

[edit]

In September 1864, Prince Edward Island hosted the Charlottetown Conference, which was the first meeting in the process leading to Confederation and the creation of Canada in 1867. Prince Edward Island did not find the terms of union favourable and balked at joining in 1867, choosing to remain a separate British colony.

In the late 1860s, the colony examined various options, including the possibility of becoming a discrete dominion unto itself, as well as entertaining delegations from the United States, who were interested in Prince Edward Island joining the United States.[20]

Canadian Confederation

[edit]In the early 1870s, the colony began construction of a railway and frustrated by Great Britain's Colonial Office, began negotiations with the United States. In 1873, Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald, anxious to thwart US expansionism and facing the distraction of the Pacific Scandal, negotiated for Prince Edward Island to join Canada. The Government of Canada assumed the colony's railway debts and agreed to finance a buy-out of the last of the colony's absentee landlords to free the island of leasehold tenure and from any new migrants entering the island. Prince Edward Island entered Confederation on July 1, 1873. The problem of absentee landowners was subsequently addressed by the passage of the Land Purchase Act, 1875.

Post-Confederation history

[edit]

As a result of having hosted the inaugural meeting of Confederation, the Charlottetown Conference, Prince Edward Island presents itself as the "Birthplace of Confederation" with several buildings, a ferry vessel, and the Confederation Bridge, the longest bridge over ice-covered waters in the world,[21] using the term "confederation" in many ways. The most prominent building in the province with this name is the Confederation Centre of the Arts, presented as a gift to Prince Edward Islanders by the 10 provincial governments and the Federal Government upon the centenary of the Charlottetown Conference, in Charlottetown as a national monument to the "Fathers of Confederation."

Religion played a central role in the development of institutions with non-denominational (i.e. Protestant) and Roman Catholic public schools, hospitals (Prince Edward Island Hospital vs. Charlottetown Hospital), and post-secondary institutions (Prince of Wales College vs. St. Dunstan's University) being instituted. St. Dunstan's was originally developed as a seminary for training priests, and the Maritime Christian College was founded in 1960 to train preachers for the Christian churches and churches of Christ in Prince Edward Island and the Maritime Provinces.

As with most communities in North America, the automobile shaped Charlottetown's development in the latter half of the twentieth century, when outlying farms in rural areas of Brighton, Spring Park, and Parkdale saw increased housing developments. The Charlottetown airfield in the nearby rural community of Sherwood was upgraded as part of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan and operated for the duration of World War II as RCAF Station Charlottetown, in conjunction with RCAF Station Mount Pleasant and RCAF Station Summerside. After the war the airfield was designated Charlottetown Airport. Charlottetown's shipyards were used extensively during World War II, being used for refits and upgrades to numerous Royal Canadian Navy warships. Further post-war development continued to expand residential properties in adjacent outlying areas, particularly in the neighbouring farming communities of Sherwood, West Royalty, and East Royalty.

To commemorate the centennial of the Charlottetown Conference, the ten provincial governments and the Government of Canada contributed to a national monument to the "Fathers of Confederation". The Confederation Centre of the Arts, which opened in 1964, is a gift to the residents of Prince Edward Island, and contains a public library, nationally renowned art gallery, and a mainstage theatre which has played to the Charlottetown Festival every summer since. The PEI Comprehensive Development Plan in the late 1960s greatly contributed to the expansion of the provincial government in Charlottetown for the next decade. The Queen Elizabeth Hospital opened in 1982. In 1983, the national headquarters of the federal Department of Veterans Affairs was moved to Charlottetown as part of a nationwide federal government decentralization programme. In 1986, UPEI expanded further with the opening of the Atlantic Veterinary College. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, there was increased commercial office and retail development. A waterfront hotel and convention centre was completed in 1982 and helped to encourage diversification and renewal in the area, leading to several residential complexes and downtown shopping facilities. The abandonment of rail service in the province by CN Rail in December 1989 led to the railway and industrial lands at the east end of the waterfront being transformed into parks and cultural attractions.

On May 31, 2021, the Charlottetown City Council voted to remove a statue of John A. MacDonald, the first Prime Minister of Canada, following a year of vandalism in the wake of the George Floyd Protests. The catalyst for the removal came following the discovery of a mass grave at the Kamloops Indian Residential School in British Columbia.[22]

See also

[edit]Further reading

[edit]- Campbell, Duncan (1875). History of Prince Edward Island. Heritage Books.; also

- History of Prince Edward Island at Project Gutenberg

- Harvey D. C. The French Régime in Prince Edward Island (Yale U.P., 1926).

- Livingston, Ross. Responsible Government in Prince Edward Island: A Triumph of Self-Government under the Crown (1931) online

- Whitcomb, Dr. Ed. A Short History of Prince Edward Island. Ottawa. From Sea To Sea Enterprises, 2010. ISBN 978-0-9865967-1-1. 56 pp.

References

[edit]- ^ "Prince Edward Island Indian Tribes and Languages". Archived from the original on 27 April 2015. Retrieved 20 April 2015., Native Languages of the Americas website. Retrieved on 2015-04-20.

- ^ Island Information: Quick Facts Archived 2011-10-21 at the Wayback Machine, website of the Government of Prince Edward Island, 2010-04-27. Retrieved on 2010-10-25.

- ^ "ACADIAN-CAJUN Genealogy & History: Ile St. Jean". www.acadian-cajun.com. Retrieved 6 April 2022.

- ^ Earle Lockerby, Deportation of the Prince Edward Island Acadians. Nimbus Publishing. 2008. p. 2

- ^ a b Lockerby, p. 3

- ^ Harvey, p. 110

- ^ a b Harvey, p. 111

- ^ Harvey, p. 112

- ^ Biography On Line

- ^ John Clarence Webster's, "Memorial on Behalf of Sieur de Boishebert" (Saint John: Historical Studies No. 4, Publications of the New Brunswick Museum, 1942) at p. 11.

- ^ "Mi'kmaw History - Timeline (Post-Contact)". www.muiniskw.org. Archived from the original on 23 September 2017. Retrieved 6 May 2018.

- ^ MacLeod, Malcolm (1979). "Legardeur de Croisille et de Montesson, Joseph-Michel". In Halpenny, Francess G (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. IV (1771–1800) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- ^ John Grenier, Far Reaches of Empire: War in Nova Scotia 1710-1760. Oklahoma Press. 2008

- ^ Patterson, Stephen E. (1998). "Indian-White Relations in Nova Scotia, 1749-61: A Study in Political Interaction". In P.A. Buckner; Gail G. Campbell; David Frank (eds.). The Acadiensis Reader: Atlantic Canada Before Confederation (3rd ed.). Acadiensis Press. pp. 105–106. ISBN 978-0-919107-44-1.

• Patterson, Stephen E. (1994). "1744–1763: Colonial Wars and Aboriginal Peoples". In Phillip Buckner; John G. Reid (eds.). The Atlantic Region to Confederation: A History. University of Toronto Press. p. 144. ISBN 978-1-4875-1676-5. JSTOR 10.3138/j.ctt15jjfrm. - ^ Lockerby, p. 7

- ^ PEI Provincial Government. "Historical Milestones". Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 17 August 2007.

- ^ Julian Gwyn. Frigates and Foremasts. University of British Columbia. 2003. p. 58

- ^ Government of Canada Archived 2007-03-25 at the Wayback Machine - PEI history

- ^ John Boileau, Samuel Cunard: Nova Scotia's Master of the North Atlantic Halifax: Formac (2006), p. 94

- ^ Francis Bolger, "Prince Edward Island and Confederation" CCHA, Report, 28 (1961), 25-30 online Archived 2012-10-04 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ The Confederation Bridge Archived 2007-02-12 at the Wayback Machine - Official Website

- ^ Kevin, Yarr (1 June 2021). "Sir John A. Macdonald statue quickly removed after Charlottetown council decision". CBC.